TCP/IP in OCaml Part 2 - Concurrency Design with OCaml Multicore and EIO

In the last two sections, we went over how TUN devices work, and I showed some local network setup that allows two tun devices to forward packets between each other. In this section, I will go over an overarching sketch of the concurrency architecture for my TCP stack, and create the skeleton for the client/TCP program interaction.

Overarching Design

My TCP implementation will have a big initial constraint: it will be a user space program embeddable within a client program, that is, an entire TCP instance is created for each client that needs to use it. We can compare this to a typical kernel level TCP implementation, that has to multiplex between multiple user programs that can be using TCP. My TCP implementation will only be concerned with the client that instantiated it. Also, it will only handle one connection at a time. The rationale is that I wont test the infrastructure for multiple connections until I have successfully implemented a single TCP connection.

Before getting to multiple connections, I also plan on writing a network simulation layer between the TCP server and the TUN devices. This will allow us to simulate dropping, duplication, and delay of packets. So for now, a single connection is just fine to do a lot of fun coding.

The client program will be exposed to a normal TCP api, for example some commands such as:

tcp_open

tcp_connect

tcp_recv

The TCP server will be instantiated on an open or connect call. It will run as a parallel thread of execution, reading/writing packets from/to its TUN device, and reading/writing messages in a channel that is set up between the client and the TCP server.

Concurrency in OCaml

My previous experience with concurrency in OCaml was with LWT cooperative threading. I am also familiar with the Thread library in OCaml, which allows you to fork a thread. The issue is that the OCaml runtime holds some sort of a lock that prevents the thread from executing in parallel with the thread that spawned it, so it allows for concurrency but not parallelism.

OCaml 5 seems to have greatly expanded support for concurrency and parallelism. For my TCP implementation, I will use two new features from OCaml 5: multicore and EIO.

Multicore

With OCaml 5 multicore, it is possible to spawn truly parallel threads. These are different from LWT threads, which are scheduled on a cooperative threading basis (so a “thread” is not supposed to run forever, it should give up its execution in some finite amount of time). OCaml multicore provides “domains” that allow you to spawn a parallel thread of execution. These are more heavyweight than the LWT coroutines, but the new thread can run on a separate core. I thought that this is perfect for a background TCP server that I am creating. Given the TCP API, I don’t want the client to have to be concerned with scheduling the TCP server along with its client code – I just want a server that is spawned, runs separately, and communicates with the client via a channel.

EIO

EIO is very cool, since it is built on top of effects. I was tempted to go into an OCaml language detour here and dig deeper into how EIO is implemented. Effects are a new language feature, which are not officially integrated with the language yet, which are a generalization of exception handling. It’s kind of like exception handling, but instead of just raising the exception you get the entire state of the computation at the point where the “exception” or “effect” is raised, and then choose what to do from there. EIO basically defines 3-4 of its own effects to build an entire cooperative threading library (two of which are named, suggestively, Fork and Yield). Whereas LWT built cooperative threading on top of monads and promises, it seems like EIO built it on top of effects and continuations. This is my rough understanding, and hopefully I will have time to dig deeper on this in a future blog post.

In terms of more practical usage, though, it doesn’t feel all that different from LWT except for the fact that the code is non-monadic in structure and I think is easier to read. One thing I didn’t quite like about LWT is my entire code base turning into monadic composition.

Putting it together

OK, now that I talked through the design let’s throw it all together and create a skeleton architecture for the TCP server.

First, I have the host client and peer client code:

host.ml

let main env =

if Array.length Sys.argv < 4 then

Printf.eprintf "Usage: %s <tunX> <tun CIDR>" Sys.argv.(0);

let tun_name = Sys.argv.(1) in

let tun_addr = Sys.argv.(2) in

let msg_stream = Tcp.tcp_init env tun_name tun_addr in

Eio.traceln "Client";

while true do

Eio.traceln "Write Conn Msg.";

let c = (Tcp.Conn {ip="10.0.1.7"; port=123}) in

Eio.Stream.add msg_stream c;

done

let () = Eio_main.run main

I still need to dispatch my entire code in an Eio_main.run, in order to pass along the environment, but the background TCP server thread creation is completely opaque in the tcp_init call. For now, a msg_stream object is returned over which the client can communicate with the TCP server. We write a dummy Conn message to the TCP server – later on this will be wrapped in a tcp_conn function.

peer.ml

open Utils

let main () =

if Array.length Sys.argv < 4 then

Printf.eprintf "Usage: %s <tunX> <tun CIDR>" Sys.argv.(0);

let tun_name = Sys.argv.(1) in

let tun_addr = Sys.argv.(2) in

let tun = Tun.create tun_name in

run_command (Printf.sprintf "sudo ip addr add %s dev %s" tun_addr tun_name);

run_command (Printf.sprintf "ip link set %s up" tun_name);

let payload = read_tcp_payload "tcp.bin" in

let packet = Ip.serialize ~protocol:Ip.TCP ~source:"10.0.1.7" ~dest:"10.0.0.6" ~payload in

let p = Ip.deserialize packet in

flush stdout;

while true do

let _ = Tun.write tun packet in

flush stdout;

let _ = Ip.pp_ip_packet (Format.formatter_of_out_channel stdout) p in

Unix.sleep 1

done

let () = main ()

The peer is set up so we can actually test out the TCP packet forwarding. I create a dummy packet using a python scapy script, with the contents stored in tcp.bin:

from scapy.all import *

tcp = TCP(sport=12345, dport=9999, flags="S", seq=1)

raw_tcp = bytes(tcp)

with open("tcp.bin", "wb") as f:

f.write(raw_tcp)

Note that I also implemented a custom IP serialization. This isn’t super interesting as it is just serializing/deserializing according to the IP header format, the code can be found in Ip.ml on my github.

Now lets get to spawning a TCP server thread:

open Eio

open Utils

module Packet = Packet

type t = {

tun: Tun.t;

}

type conn = { ip : string; port : int }

type msg = Conn of conn

let tcp_server _ _ tun_name tun_addr msg_stream =

traceln "TCP Server";

let tun = Tun.create tun_name in

run_command (Printf.sprintf "sudo ip addr add %s dev %s" tun_addr tun_name);

run_command (Printf.sprintf "ip link set %s up" tun_name);

(* Handle TUN device input. *)

let tun_fiber = (fun () ->

traceln "Read TUN Packet";

let buf = Bytes.create 1500 in

while true do

let packet_size = Tun.read tun buf in

let packet_bytes = Bytes.sub buf 0 packet_size in

let packet = Ip.deserialize packet_bytes in

match (packet.version, packet.protocol) with

| (Ip.IPv4, Ip.TCP) ->

Ip.pp_ip_packet (Format.formatter_of_out_channel stdout) packet;

flush stdout;

| _ -> ();

Fiber.yield ();

done;

()

) in

(* Handle user communication. *)

let user_fiber = (fun () ->

traceln "Read Client Msg.";

while true do

let msg = Eio.Stream.take_nonblocking msg_stream in

match msg with

| Some (Conn _) -> traceln "Got Conn!";

| None -> Fiber.yield ();

done;

) in

(* Wait for both fibers to finish (although they have infinite loops, we await them to ensure the program doesn't exit). *)

Eio.Fiber.both tun_fiber user_fiber

let tcp_init _ tun_name tun_addr =

let msg_stream = Eio.Stream.create 3 in

ignore (Domain.spawn (fun () ->

Eio_main.run ( fun env ->

Eio.Switch.run (fun sw ->

tcp_server env sw tun_name tun_addr msg_stream;

);

)

));

msg_stream

The TCP init function creates the parallel thread with a domain spawn. Then, within that “domain” or parallel thread, I create a new EIO context. The idea here is that although we are spawning a parallel thread for the entire thread server, I thought it would be good to have the TCP server itself be implemented using cooperative threading via EIO. The msg_stream object is used for the client and server to communicate, and is passed along to the server as well as returned to the client. For testing purposes, I set its buffer size to 3 messages for now.

Now if we look at the TCP server function, we can see the cooperative threading at play. The function runs two threads – tun_fiber and user_fiber. Nothing to do with nutrition, this is some EIO terminology I still have to get better acquainted with. Each of these is an infinite while loop that waits on either reading a message from the channel (for new, it checks to see if there is a dummy Connection request incoming from the client), or reads a packet from the TUN device. The peer.exe will be sending packets, so we should expect to read them here.

If we execute host and peer at the same time, we get the following output on the host:

(client)+Write Conn Msg.

(TCP server)

IP Packet:

Version: IPv4

IHL: 5 (words)

Total Length: 40 bytes

Source: 10.0.1.7

Destination: 10.0.0.6

Payload Length: 20 bytes

Protocol: TCP

(TCP server)

+Got Conn!

(client)

+Write Conn Msg.

We can see an interleaving of operations going on. The client is writing a connection message to the TCP server, and the TCP server is both reading from the TUN device and reading the client’s connection message in a cooperative threading manner.

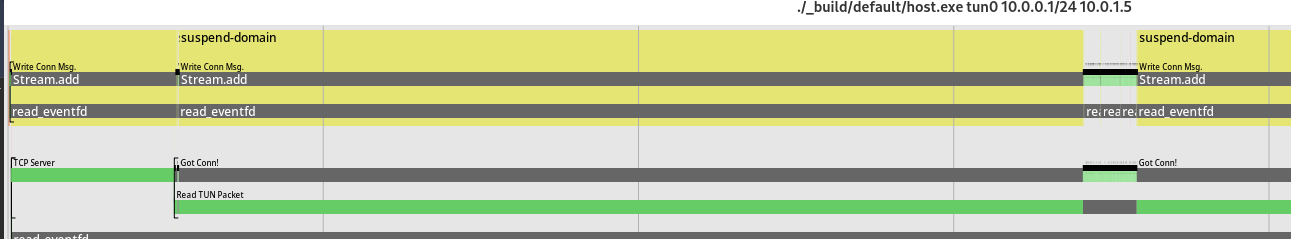

To top it all off, one of my favorite features that comes out of the box with EIO is the tracing visualizer. I can add informative print statements and get a sense of how the parallel and concurrrent execution is playing out:

trace-host:

env PATH=$$PATH eio-trace run -- ./_build/default/host.exe tun0 10.0.0.1/24 10.0.1.5

We can see two different “domains” or threads running in parallel. The top one corresponds to the client, so it appears to show points where a connection message is written. The TCP server thread, on the bottom, shows the points where a connection is received or it is reading a TUN packet. I’m excited to learn more about this tool!